Lynn’s Review

How Chemical Dyes Changed the West’s Relationship with Food

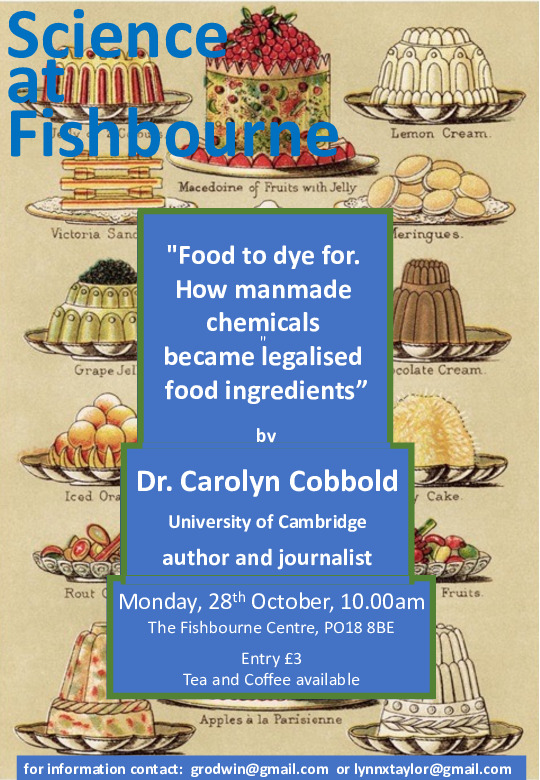

Food is of interest to us all, and Dr Carolyn Cobbold’s presentation to Science at Fishbourne generated many questions from us, whilst also revealing that many of us read through the ingredients listed on foods before we decide to buy.

Food is a combination of chemicals, generally natural chemicals, but man-made chemicals are now found in most foods, and the question of what is good for you and what is harmful changes as science and knowledge changes.

We discovered many interesting facts from the history of food production; the preservatives and dyes introduced over time, but it was a revelation to discover that Napolean III, was in part, responsible for the introduction of the butter substitute: margarine! He was the first president and last emperor of France; a popular monarch, who oversaw the modernization of the French economy. He also instigated a competition to find a cheap substitute for butter which would provide energy for his troops, and for the workers who were now moving from the land to work in the towns.

In 1869 Hippolyte- Mege-Mouries, won the competition when he managed to combine beef tallow with milk.

Margarine continues to be produced today, being made from a variety of vegetable oils and fat based products and perception as to whether it is good for you varies from person to person. In the same way, E numbers present confusion:

from Wikipedia: “In the UK, food companies are required to include the 'E Number(s)' in the ingredients that are added as part of the manufacturing process. Many components of naturally occurring healthy foods and vitamins have assigned E numbers (and the number is a synonym for the chemical component), e.g. vitamin C (E300) and lycopene (E160d), found in carrots. At the same time, "E number" is sometimes misunderstood to imply approval for safe consumption. This is not necessarily the case, e.g. Avoparcin (E715) is an antibiotic once used in animal feed, but is no longer permitted in the EU, and has never been permitted for human consumption. Sodium nitrite (E250) is toxic. Sulfuric acid (E513) is caustic.”

The European Union began to regulate food in 2002 with “The General Food Law Regulation,” and in 2016 introduced legislation which presented food producers with the obligation to provide nutrition information to the consumer. They weren’t the first to regulate though, for: In 1202, King John of England proclaimed the first English food law: “The assize of bread,” which prohibited adulteration of bread with such ingredients as ground peas or beans.

Although there was much confusion when Britain left the EU. Food safety standards still apply.

Artificial colours were the first man made chemicals legitimised for foods. A purple dye called mauveine was discovered in 1856 by William Henry Perkin, an 18-year-old chemist, and research assistant to August Von Hofmann at the Royal College.

Hoffmann was attempting to make a synthetic form of quinine from coal tar and Perkin worked on this. He tried to oxidise aniline using potassium dichromate and, in the process, discovered the resulting solution turned silk purple.

Synthetic dye factories soon sprung up and the magic of colour entered the Victorian world. Frank Baum’s film; “The Wizard of Oz,” gave a visual insight into the impact of colour at that time.

These aniline dyes were initially used for textiles, they were welcomed because the colours didn’t fade like natural dyes. By 1897 it was estimated that there were 900 different dyes sold under 8000 trade names. It was little wonder that the natural dyes used in foods were gradually replaced by the aniline dyes, with no knowledge as to possible harms from them.

In 1830, people lived in villages; they grew their food, or knew where I came from; by 1860, people were now in cities and there was a much longer food chain, so allowing extra money to be made at each stage. As well as adding water to milk to make it go further, or flour to mustard, dyes would improve the look of food, or maybe even extend the shelf life of food.

Concern for the safety of the dyes had been growing since the 1870s. Initially, perhaps from dyed clothing producing skin rashes, and then from children suffering poisoning from coloured sweets. Food chemists were appointed to check food for safety. Generally, it was easier to blame, “Foreign food.”

In France, the chemist Charles Girard, identified 7 possibly harmful dyes used in wine and they were banned, but this meant that all other untested dyes were now considered safe.

Similarly, in Germany, where engineering and synthetic dye production companies were successfully established, it was vital that the consumer saw that dyes were safe. Banning metallic dyes in 1887, and investigating the dyes in sausages in 1899, led to the same result achieved by French regulators.

In the USA, margarine became the focus of attention as it looked so like butter. Five states declared that it must be pink rather than yellow. The USA’s approach to dye safety was different; seven dyes, considered to be safe, were identified, and only these were allowed to be used, however, just before these were legalised, four of them were changed!

Britain, chose to leave it up to the lawyers who took people to court for deception (my own great grandfather was fined £91 for deception, when he sold margarine as butter in 1899.) Leaving decisions to the law, heralded the introduction of “Expert witnesses” to court cases, corruption also, no doubt, entered the scene.

Politics, economics, trade, media, and consumer preferences, all now play their part in food production. There is no true transparency as to what is safe/not safe. We now have chemicals in foods that didn’t exist prior to the 19th Century, and it’s not just the foods but also the livestock and crops which are subjected to chemicals and antibiotics, and, as we know from previous talks, human waste charged with pharmaceuticals is used to fertilize crops.

To end on a lighter note: Despite this, I think we are living longer, ’though I’m sure this statement could be the starting point for much discussion.